Revolutionary War-Martin’s Station Fort-Lee County, VA

Filed Under : Local History by Jeff Roberts

Filed Under : Local History by Jeff Roberts Aug.31,2010

Aug.31,2010Originally posted at http://www.danielboonetrail.com/historicalsites.php?id=46.

The Revolutionary War was fought on two fronts; from its beginning in 1775, until the treaty of peace in 1783, it was fought on the western front against the Indians, chiefly by the pioneers of Kentucky and frontiersmen of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the Carolinas. It was fought in a more conspicuous theatre along the Atlantic seaboard by the colonists against the British regulars.

Curiously enough, almost exactly at the time of the firing of the first gun of the Revolution at Lexington, Massachusetts, the Wilderness Road was connected up into a bridle path, which joined the western Virginia border with Central Kentucky. ?This alone made Kentucky’s settlement possible, at that time, and that settlement, in turn, furnished the necessary base for the conquest of the Northwest by the frontiersmen under George Rogers Clark. The road is significant, therefore, not only in the history of Kentucky, but in that of the Revolutionary War.

Martin’s Station was the feature of man’s providing on the road that was most important in making it a practical way into Kentucky. It was a long, hard road. The road through the wilderness began at the blockhouse, which faced Moccasin Gap, where the Indian country began. It ran its winding course through valleys and along creeks, across the Holston, Clinch, Powell, and Cumberland rivers; over Powell Mountain and Wallen’s Ridge (as difficult as Powell Mountain), down Powell Valley, over Cumberland Gap, through the gorge where the Cumberland River cuts its way through Pine Mountain, and then through the foothills until it reached the plateau of Central Kentucky at Crab Orchard and Berea.

Its course had been followed, in a general way, by a few hunters and land lookers in the ten years before 1775, but it was definitely marked to Boonesborough by Boone, when he led the party for Col. Henderson and the Transylvania Company from Long Island to Boonesborough in March and April 1775.

Its whole course, from the time it passed Moccasin Gap, was in a country which the Indians infested. They resisted the invasion by the whites, not only to protect their hunting ground, but at the instigation of the British, who recognized the danger to their hold on the West by the thrust of the Kentuckians into the heart of it.

For the 200 miles of the course of the road through the wilderness, there was neither Indian nor white settlement. There was no base of supplies and no refuge, save only at one spot, and that was Martin’s Station in Powell Valley. That was what made Martin’s services in the establishing of his station along the Wilderness Road so important.

Martin’s Station was located 20 miles eastward of Cumberland Gap. It was the halfway house between Virginia and Kentucky; the lone station midway of the journey through an uninhabited district. Every traveller over the road had the support of Martin’s Station on his mind, and those who made written records of their journeys mention it in a way to indicate the importance attached to it.

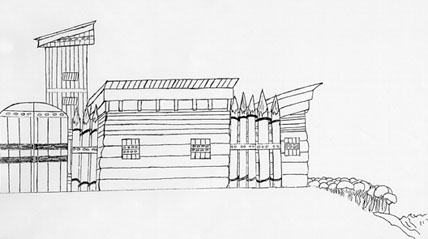

The station was located exactly on the Wilderness Road where it crossed a creek, later called Martin’s Creek, in Lee County, Virginia. The present state road between Boone’s Path on the east, a third of a mile away; and Rosehill on the west, half a mile away, passes through the old station grounds.

The cabin stood on a low mound about 70 yards to the east of Martin’s Creek, a stream big enough, as Martin said, “to turn a mill;” and 30 yards from a bold, overflowing spring, both of which were doubtless included within the stockade of the station.

Martin was born near Charlottesville, in Albermarle County, Virginia, in 1740, of an affluent family. From boyhood, he took to Indian adventure, and it is probable that he entered Powell Valley as early as 1761.

In 1769 he was allotted, by Dr. Thomas Walker, 21,000 acres for the first settlement in the valley, and in the endeavor to hold this land, he undertook to found a station there in the spring of 1769. The station was attacked by Indians. As a result, it was abandoned in the fall of the same year.

In January 1775 Martin went back with a party of 16 or 18 men and built a station, which included four or five cabins for the men and a stockade on exactly the old site. Thereafter, the station remained, although, at times, unoccupied throughout the period of the early emigration to Kentucky.

The reestablishment of the station in January 1775 was, perhaps, in anticipation of the organization of the Transylvania Company, which was consummated in March of that year. Whether that is so or not, when Boone (and a little later, Henderson) went to Kentucky with their parties in the spring of 1775, Martin was at his station; and furnished a base for the final journey into Kentucky.

He effectively cooperated with Henderson throughout the existence of the Transylvania Company. Henderson, indeed, seems to have used Martin, the executive and diplomat with the Indians, as his business agent at this outpost; as he did Boone, the hunter and explorer, for leading his expedition into Kentucky.

In 1777 Martin reestablished himself at his old station, where he conducted Indian affairs for a wide district, until he retired as Indian agent in 1789.

Martin’s Station is well-known to students of the Wilderness Road, but Joseph Martin had no Filson to celebrate his feats, as Boone had, and he has been almost forgotten. Professor Stephen B. Weeks, of Johns Hopkins, resurrected him in an accurate biographical sketch, which he read before the first meeting of the American Historical Society. But this, in turn, was buried in a government report.

Martin’s work in connection with Martin’s Station and the emigration to Kentucky constitutes only a small part of the accomplishments, which entitle him to be remembered. He was not only one of the most important men in Indian affairs, but in all public affairs in western Virginia and North Carolina. Until 1789 he was chiefly engaged with Indian business. After that time he was a leader in public affairs, in general, on the southwestern frontier.

In 1777 Gov. Patrick Henry commissioned him agent and superintendent of Indian affairs for the state of Virginia, a position he retained until 1789. Because of his influence in restraining the Cherokees, he, more than anyone else, kept the Indians off the backs of the settlers on the Virginia and Carolina frontiers and left them free to cooperate with the other colonial troops against the British in the South. That made victory at King’s Mountain possible, and that, in turn, assured a few months later, the hemming in and capture of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Until he was nearly 60, Martin was engaged in all sorts of public affairs in a way that marked him as a leader: Indian agent (not only for Virginia, but also for North Carolina), on peace commissions, on boundary commissions (notable that on the western boundary between North Carolina and Virginia, and that between Virginia and Kentucky); brigadier general on appointment of Gov. Henry Lee, of Virginia, and for many years in the Virginia Legislature.

He gave up participation in public affairs in 1779, in his 60th year, and retired to his estate in Henry County, Virginia, where he died on December 8, 1808, in his 69th year.