Witcher’s Boys in Lee County During the Civil War

Filed Under : Family Stories by Jeff Roberts

Filed Under : Family Stories by Jeff Roberts Jul.23,2020

Jul.23,2020Here is a story about Confederate “Bushwackers” in Lee County during the Civil War, courtesy of Lawrence J. Fleenor at http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~duncanrw/witchersboys.html

Witcher’s Boys in Lee County During the Civil War

By: Lawrence J. Fleenor

October 1997

At the beginning of the American Civil War the mountainous region between Kentucky and Virginia did not fit comfortably into either the Union or the Confederacy. About a third of the people sympathized with the Confederacy, another third were pro Union, and the remainder just wanted to be left alone. Indeed, the northwestern portion of Virginia was to break away before the end of the war and form the state of West Virginia.

The parents of this generation had fought the bloody Indian Wars, and were heavily intermarried with the Mingos to the north and with the Cherokee to the South. Bushwacking and obligatory revenge killings…(transcriber note: It appears part of the paragraph is missing from the original document.)

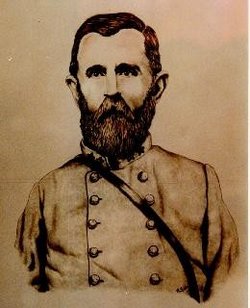

Born February 16, 1837 in Pittsylvania County in Southside Virginia, he studied law a while and in the spring of 1860 moved to Wayne County, Virginia in what is now West Virginia. He was known throughout his adult life as “Clawhammer” because of the style of scissors tail dress coat he always wore. It proved to be an appropriate nickname, because he left wreckage in his wake where ever he went.

Clawhammer gathered a small number of pro Confederate men about himself, and began to engage in the free for all on the Kentucky border. Similar pro Union paramilitary bands also marauded in the area. Initially neither of the national governments recognized these guerilla bands, and if a man were captured from these units, they were frequently executed because the protection of the Articles of War did not apply to them. To afford their own bushwhackers the protection law, both the Federal and Confederate governments gave their bands official military status. Clawhammer’s men thus became designated the “34th Battalion Virginia Calvary, CSA.”

Initially labeled as “Independent Scouts”, the unit became known as “Witcher’s Boys.” It was their duty to serve as a counter insurgency force against the local Union units operating in West Virginia, East Kentucky, Southwest Virginia, and Northeast Tennessee. They soon began to distinguish themselves for their barbarity, their specialty being a variation of lynching done with a bent pole that jerked its victim into eternity.

At this point in the War, all men between sixteen and fifty were either in the Union or Confederate Armies or were draft dodgers hiding out in one of the numerous small bands of roaming marauders, or were “scouting out” individually in the mountains, hiding from the approach of all but loved ones who brought them food. Therefore, any man Witcher’s Boys found in these counties was presumed to have been either a deserter, a draft dodger, a spy, or the member of an opposing guerilla band, and could be shot without a trial. Clawhammer and his Boys seemed to have played their role with such enthusiasm that even Confederate General John B. Floyd said of them, “V.A. Witcher collected a band of 17 or 18 men, calling themselves partisan rangers. Instead of affording protection and safety to the property of persons of loyal Southern men, this company rendered themselves an object of fear and terror to the entire population, whether Union or Secession. Their deeds of plunder and robbery fell alike on those true or untrue to the South. They became to be viewed as a set of robbers and deprecators, banded together solely for the purpose of plunder, and acting without authority of law or order.”

So it was that on July 7, 1862 Witcher and his Boys were in Lee County rounding up men suspected of pro Union sentiment. There had many raids in other parts of Lee County, but this day as on other occasions Wallen’s Creek was their special target. A man named John “Jack” Miers, aged 32, was captured by Witcher’s Boys under the immediate command of a man named “Rowan.” Also, a man named John Davis Sage, aged 45 and whose wife was Sarah and had children, had been to the mill when they were accosted by Witcher’s Boys. They took Jack and Davis into custody. Another man named James P. Smith, whose wife was Martha Myers, and who had children, and who had also been to the mill. She was the sister of Jack Myers. Witcher and his Boys stole Smith’s fine team of horses. Smith followed Witcher’s Boys down the road and begged for his horses back, and on Powell Mountain they shot and killed him. They gathered up a group of thirty to forty men and incarcerated them in the log Blue Spring Church in Stickleyville for the night. Two of the smaller men thought they could escape by lifting a puncheon from the church floor and crawling out. Some of the captives held the puncheon up and let the two men escape. The next day Witcher’s Boys took the remaining prisoners including Myers, Sage, and the others including a man named James Berry out on Powell Mountain and killed them. It was some time before they were found and the bodies were hard to identify. One man had been hanged, and Sage was decapitated. Sage was identified only by the underwear that his wife had made for him. Some of these men were buried in the Duff Cemetery at Stickleyville.

The large hollow tree that had stood in front of the Stickleyville church at the time of this incident has only been recently cut down. One can still see the charring on the stump made by the fire that Witcher’s Boys built around it on that night so long ago. The tree itself lays on its side and shows within its hollow the char from the fire that was drawn up within it like a chimney.

After fighting creditably in the Battle of Gettysburg, late 1863 found Witcher, now a Lieutenant Col. Back in East Tennessee. In January 1864 Witcher came up from East Tennessee to help Col. Pridemore at the Battle of Jonesville. That April, a CSA military court removed him from command because of charges brought by General W. E. “Grumble” Jones, but intervention by Brig. General John Hunt Morgan got him reinstated.

During the Civil War, William H. and Polly Tritt Hughes lived near Dry Branch north of the highway just east of Pennington Gap. Even though their two sons were serving in the Confederate Army, another two of their sons named David L., aged 26 and unmarried, and a brother named William Hughes, aged 39 and who was married and had children, were among several neighborhood men who had moved to Ohio to avoid being drafted into the Confederate Army. However, David and William returned home so that David could see his girlfriend, a Yeary girl.

They did not stay in the home of their parents, but boarded with a neighbor, Joe Ely, whose double pen log cabin connected by a dog trot lay in the hollow under the hill where “Billy Dad” Yeary and his daughter lived. While they were in they went to a saloon run by a Spangler woman at Big Hill. Somehow, the saloon burned and the woman blamed the Hughes boys for it. At this time, Witcher and his “Boys” came up from Tennessee looking for draft dodgers from the Confederate Army, and spoke to the woman asking her for names of men in the area who he might want to look up. She gave him the names of the Hughes boys.

On December 11, 1864 Witcher’s Boys surrounded the Joe Ely home. They threatened to burn it down to get the Hughes brothers to come out, but because of the presence of children, they Hughes surrendered peacefully.

Soon after this, Nimrod Ely, then aged nine, was sitting on a snake fence and saw the Hughes brothers being carried off by Witcher’s Boys on the Road to Rocky Station by Big Hill. At Big Hill the Hughes brothers were clubbed to death with stones. Traditionally, the names of two Witcher’s Boys who did this were a Bailey and a Spurlock.* After the initial clubbing, Witcher’s Boys started to leave but one of the Hughes brothers was observed to be on his knees praying and one of Witcher’s men dropped back and finished him off. A sister of the Hughes boys followed them later, and caught up with them at Big Hill. One of the brothers was already dead, and the other was dying. The sister held her brother’s head in her lap as he died. She was threatened by Witcher’s Boys but unharmed. The Hughes Brothers were buried in the Hughes Cemetery to the east side of Dry Branch.

A few days later two of the men who had clubbed the last life out of the Myers (sic) brothers were involved in a card game at Dominion above St. Charles and one of them got into a shooting, and himself down on his knees, pleading for his life, and his assailant told him that he had given no mercy to the Hughes men, and shot him dead. For some reason, lost to memory, the slain man was buried in the same cemetery as s the Hughes brothers. This caused a division within the Hughes family, and years later when David and William’s brother Tobias Hughes died, he was buried in the neighboring Ely Cemetery rather than in the Hughes cemetery, because the murderer of his brothers was buried there.

In the last month of the War, Witcher was still rounding up men who were “scouting out” in Powell Valley, and carrying them off to oppose Stoneman in his second raid out of Tennessee into Virginia.

After the War, Witcher was admitted to the Tazewell County, Virginia bar, but in 1870 he moved to Utah. He returned to West Virginia and later back to his home near Riceville, Virginia, where he died peacefully in his bed, December 12, 1912.

*Footnote: Two of the Witcher’s Boys involved in the killing of the Hughes brothers were initially identified as “a Bailey and a Spurlock.” On the muster roles of the 34th Battalion of the Virginia Calvary (Witcher’s Boys) there are listed six Baileys, and only one Spurlock – all from Tazewell County, Virginia. The Baileys are: Cloyd, Green, J. D. (probably John or James based on census records), Lewis, Rufus, and Thomas S.; while the lone Spurlock is Thomas. Bibliography: Addington, Luther F. The Story of Wise County, Ball, Bonnie- “Historical Sketches of Southwest Virginia”, pub. 15; Cole, Scott S. – 34th Battalion Virginia Calvary; Interviews and family documents supplied by the following: Ruby Bailey, William T. Hughes, Sr., Jessie Myers, and Kitty Schuler.

Read more about Colonel Vincent Addison Witcher at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/67967968/vincent-addison-witcher

You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.